“It is going to be a rough and bumpy ride to 2023” ― Anthony Obi Ogbo

How can a lame-duck president with zero legislative support lead a people out of system inequality in a predominantly hostile political environment? In a democracy, the president does not have the authority to make laws or facilitate major structural transformations. The Igbo community is yearning for equal justice and equity through sweeping governance restructure. So, what kind of candidates or parties should they be looking for? Are they better off backing an immobilized president with Igbo DNA or negotiating with a congressional majority to push their agenda?

In the past six years, major Igbo political leaders encouraged the combative agitation for statehood stirred up by a separationist group, the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). Elected Igbo representatives or officials used IPOB and their often extremely divisive crusades for political convenience. However, they did not weigh some long-term political implications of those messages.

For instance, IPOB championed violent “no-referendum-no-election” operations that unleashed bloody violence at political rallies and polling stations where election workers and individuals were simply participating in the process. IPOB also recklessly destabilized the commercial sector in the Southeast. Most Igbos ignored numerous warnings from political observers about the long-term destructive nature of the trend of pushing forward their agenda of a national system that would serve their communal interests.

Astonishingly, just recently, a few months before the general election that would usher in another regime, the Igbos have been all over Nigeria’s political scene grappling with how to align themselves to attain relevance. The group has been unsuccessful in its negotiations to attain a presidential ticket in the two major political parties. However, Peter Obi, a charismatic former governor of Anambra State, defected a few days before his People’s Democratic Party primaries to become the Labor Party’s flagbearer.

Obi’s candidacy soon picked up unprecedented momentum among the youth, especially those of his Igbo ethnicity, who are now mobilizing themselves for a historic voter-registration drive to push his candidacy. Strangely enough, the same activists who championed the movement to isolate the Igbo youths from the political process because they wanted a Biafra are now flying the Labor Party flag and leading the “Obi-kere re nke” campaign mantra in a push for an Igbo president. It was precisely this cause that they had opposed for over six years. So, where does this leave the Igbos?

The purpose of this article is not to predict the electability of any candidate, nor is it to sugarcoat the prevailing rocky political environment; rather its goal is to provide some empirical insights as well as lay a more realistic foundation to enable competent Igbo thinkers to explore the prevalent political options before making any meaningful decisions about the 2023 general election.

In a democracy, interest, not tribe, drives party affiliation and support

Politics facilitates communal interests. In a democracy, interest, not tribe, drives party affiliation and support. In other words, communities look for candidates who have the capacity to make decisions not just on their behalf but also in accordance with their interests. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to first identify the interests of the Igbos.

The majority of the problems Igbos are facing today originate from the country’s constitution and its current governance structures. In a nutshell, their demands focus on the following:

-

- Reconstruction of the current constitution to impartially address revenue and resource allocations, electoral maps, the structure of state and local governments, and the draconian federal character.

- Reconstruction of the current constitution to overhaul the current security structure and decentralize internal security.

- Laws to protect Nigerian citizens, their families, homes, and businesses in every part of the country.

- Laws to address marginalization or quota and guarantee equal opportunities to all Nigerians

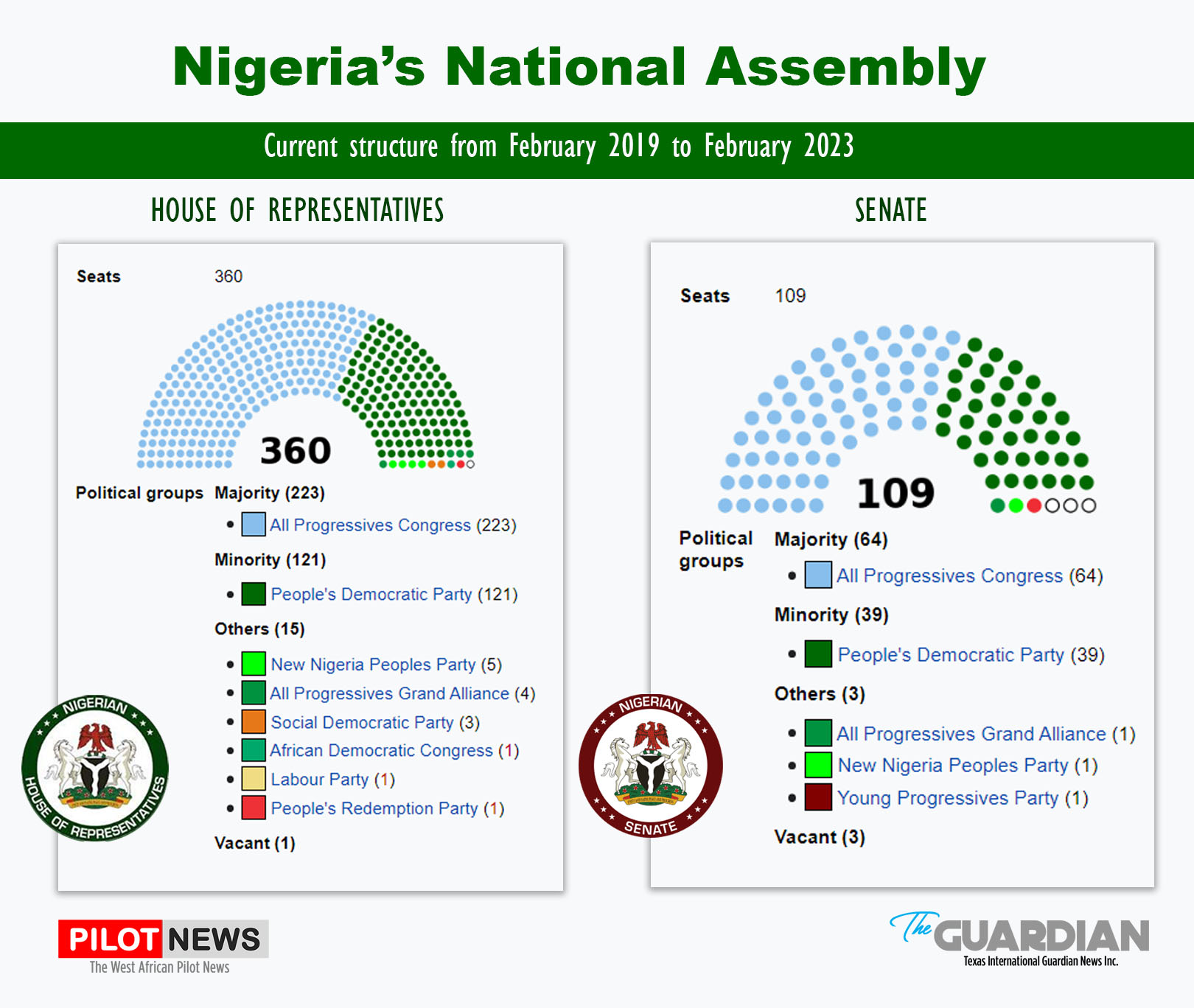

With the aforementioned crucial needs, how could voting for a lone candidate without considerable legislative support help the Igbos? In Nigeria’s organizational structure, the executive function does not make the laws; it carries them out. The judiciary evaluates the laws but often has the power to preside over very crucial decisions. The National Assembly, which consists of a Senate with 109 members and a 360-member House of Representatives, exerts much power in making structural changes. In fact, should the President reject a bill, the Assembly could pass it by two-thirds of both chambers and overrule the veto —in which case, the President’s consent would not be required.

Under the current legislative structure, in the Senate (109 seats), the All Progressives Congress (APC) has 66 seats; the People’s Democratic Party occupies 38 seats while others have 2 seats and 3 vacant seats. In the House of Representatives (360 seats), the APC occupies 227 seats; the People’s Democratic Party has 121 seats while others have 11 seats with one vacant seat.

There are Igbos advocating for individual candidates and others embracing the Labor Party to appease their strong desire for an Igbo president. The latter needs to bear in mind that, currently, the Labor party has no seat in the Senate and only one seat in the House of Representatives. Is the Labor party projecting to win significant seats in the forthcoming election? If not, how could a president of Igbo descent, with one shaky legislative seat out of 360 help the Igbos under the current constitutional structure?

It may also be interesting to note that anytime a national election is polarized along tribal lines, the first major loser is the Igbo tribe because they do not have the numbers to succeed nationally, and they are not trusted by other regions to collaborate in good faith. The much-hyped rotational presidency is not a constitutionally mandated process but an arrangement by political parties. Thus, legislative support is needed to enshrine most of the demands of the Igbos in the constitution.

It might be hard to swallow, but the truth is that the problem of the Igbos is not in Aso Rock but lies within the legislative axis. The current get-out-and-register exercise inspired by Obi is commendable, but a harsh truth remains: it is going to be a rough and bumpy ride to 2023. Igbos must set aside their emotions and put on their rational, critical-thinking caps to play hardball politics.

___________

♦Publisher of the Guardian News, Professor Anthony Obi Ogbo, Ph.D. is on the Editorial Board of the West African Pilot News. He is the author of the Influence of Leadership (2015) and the Maxims of Political Leadership (2019). Contact: anthony@guardiannews.us