Yet, here I am still standing, pledging allegiance to NIGERIA with all sense of patriotism—a nation still being governed by some of the leaders that masterminded the devastating genocide I survived 53 years ago.

Evacuating a large family from the village, Achala, to remote farmland called Eziobibi, almost twenty miles away on foot, and through near inaccessible road-paths, and under severe weather conditions was not a joke. I was seven at the time, and I walked with a loaded bag unaided. Bomb booms and some crackling sounds of artilleries rattled my nerves as they loomed from afar. This was a flight for life and concessions for being a kid were off the table.

My immediate younger sister was five and was on her feet too. I was not carrying a time clock, but a journey set out in the wee hours through the sunset would have exceeded twelve hours. We made it on foot, and for the records – I was seven, and my sister was five.

Ever since the death of Ikemba Odumegwu Ojukwu who led this war, the print, electronic and social media have been agog with analysis and historical compositions about this leader, and his unfulfilled dreams of Biafran nationhood. With commentaries controlled by emotions and different socio-political interests, it becomes difficult at times to comprehend the physical and psychological realities of three-year bloody combat that decimated the people of Eastern Nigeria, their culture, and their prospects as a region.

Nonetheless, the most compelling opinion remains an eyewitness account of the individuals who fought in the region called Biafra

Psychologically speaking, it is obvious that different experiences underscore different analyses. For instance, those Nigerians who lived during this war and never experienced it speak from Google and Wikipedia. Those who remained overseas while the Igbo people in Eastern Nigeria underwent a genocide would speak from Timelife documentaries, and those who saw, or fought the war in Biafra would speak with emotions or anger.

Nonetheless, the most compelling opinion remains an eyewitness account of the individuals who fought in the region called Biafra; those victims who survived the refugee camps, who thrived in the forest region of various villages for thirty months under thunderous sounds of shelling booms, and rapid-fire of Russian-made raffles.

Yes, I was a child victim of the Biafran civil war, and my testimony came from memory rather than Google. As a 6-year old before the war and a 9-year old after, who also survived the post-war era, it is sometimes difficult to sit on the same panel of discussion with peers who lived normal lives in the same period in the war-free Nigerian territory. They would make you feel guilty or look at you as some unpatriotic nincompoop – a Biafran loyalist that is. Sometimes they argue from the rear in a sheer fallacy or even recite doctored Internet information or adulterated opinions retrieved from nowhere.

Without reaching any search tools, I can speak from the memory of this horrible past that I saw it all with my naked eyes. I was in Kindergarten when the initial war campaign started, and Coal City was under bombardment by fighter and bomber jets operated by White mercenaries. Trenches were dug in the schools to provide safe areas against fighter plane attacks. The teachers would always remove our white shirts, and throw us into these trenches anytime the bomb alerts went off. This was the initial stage.

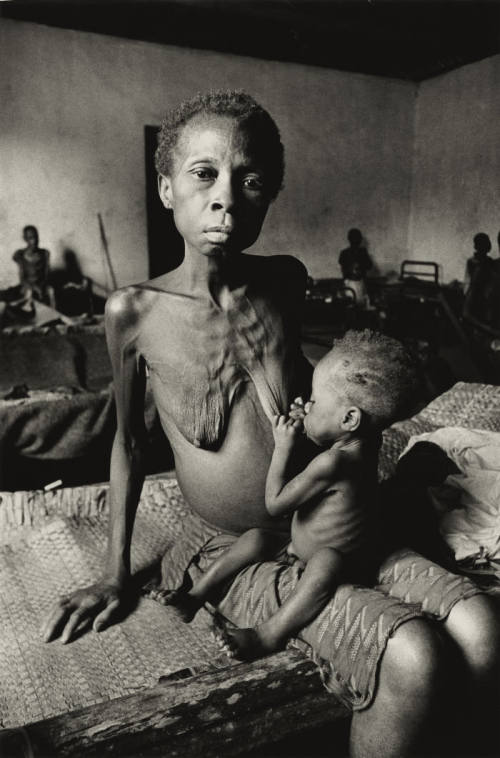

As a child during that war, I witnessed dead bodies, wounded soldiers, hungry and sick refugees eager to eat just about anything. In Achala, Awka province, where I survived the war, refugees trooped in thousands, and relief workers fed them with cornmeal. A bowl a day could do for a person, and when supplies ran out, refugees walked around the town for anything chewable. I saw refugees feed on lizards, insects, rats, and just about anything that could ease a devastating need for survival. I also saw sick ones who got so sick out of malnutrition or other strange diseases. This was the time I knew about Kwashiorkor – severe energy malnutrition typified by insufficient protein consumption. It was a sorry sight to see my fellow kids crawling with protruded bellies, and emaciated body frames visibly revealing their ribs.

As a child, I stood awake with others, sleepless at nights for fear of unexpected bombardment. I knew what assault rifles looked like; saw how bombers descended from nowhere and dropped bombs at market places. Yes, I can recall the day we were playing kite in grand dad’s gigantic compound and two bomber planes descended from nowhere and flew over. The noise alone could till a rocky ground – then as these flying equipment vanished into a cloudy sky, a shocking sound trailed. Moments later we learned that a busy Otuocha Market was bombed, and bodies were crushed like roaches – eloquent of the fact that the Nigerian troops targeted civilians. This was just a tip out of a devastating 30-month horrific experience as a child who did not go to the war field but suffered it all.

Kids went to school barefooted, while others stayed home because their parents could not afford tuition, books, and uniforms.

Yet the worst was yet to come after the war in 1970. We were hauled back to a city we left three years back. A city now devastated by the war was left without basic amenities. School buildings, churches, and homes were torn apart by shelling and other destructive devices of the war. I attended school under the trees at times and classes shifted at intervals to secure a comfortable shadowed spot. Pupils brought their desks to school because there was just none at the time.

Kids went to school barefooted, while others stayed home because their parents could not afford tuition, books, and uniforms.

Now, this was the war I saw and survived. Yet it is more distressing to have gone through this ordeal as a child without a single post-war traumatic therapy. I could just close my eyes and think of what it is like for a young child to be in traumatic situations. He can feel helpless and passive. He could have the most difficulty with their intensely physical and emotional reactions; he could just lose out in the process of coping with ongoing threats to his survival; he could not afford to trust, relax or fully explore his feelings, ideas, or interests.

Yet, here I am still standing, pledging allegiance to NIGERIA with all sense of patriotism—a nation still being governed by some of the leaders that masterminded the devastating genocide I survived almost 50 years ago.

Young trauma victims often come to believe there is something inherently wrong with them; that they are at fault, unlovable, hateful, helpless, and unworthy of protection and love. Such feelings lead to poor self-image, self-abandonment, and self-destructiveness. Ultimately, these feelings could leave them vulnerable to subsequent trauma.

Yet, here I am still standing, pledging allegiance to NIGERIA with all sense of patriotism—a nation still being governed by some of the leaders that masterminded the devastating genocide I survived almost 53 years ago.

Now, for those who do not understand what this means to an average IGBO man, and who would sit down and utter insensitive analysis about the realities of this war without consideration of the unnoticed ravages of its outcome; I will say bring it on and I will eat you raw!

♦ Professor Anthony Obi Ogbo, Ph.D. is on the Editorial Board of the West African Pilot News. Article included Excerpts from my documentary, Biafran War – What I Saw With My Naked Eyes (2011).

- ISWAP’s Explosive Device Kills 8 Civilian JTF Members in Borno - April 28, 2024

- Anambra police nabs 16 cultists, declares 21 wanted - April 27, 2024

- Anambra 2025 Governorship Election Might Be an Open Contest - April 24, 2024